Monica in Winter

1.

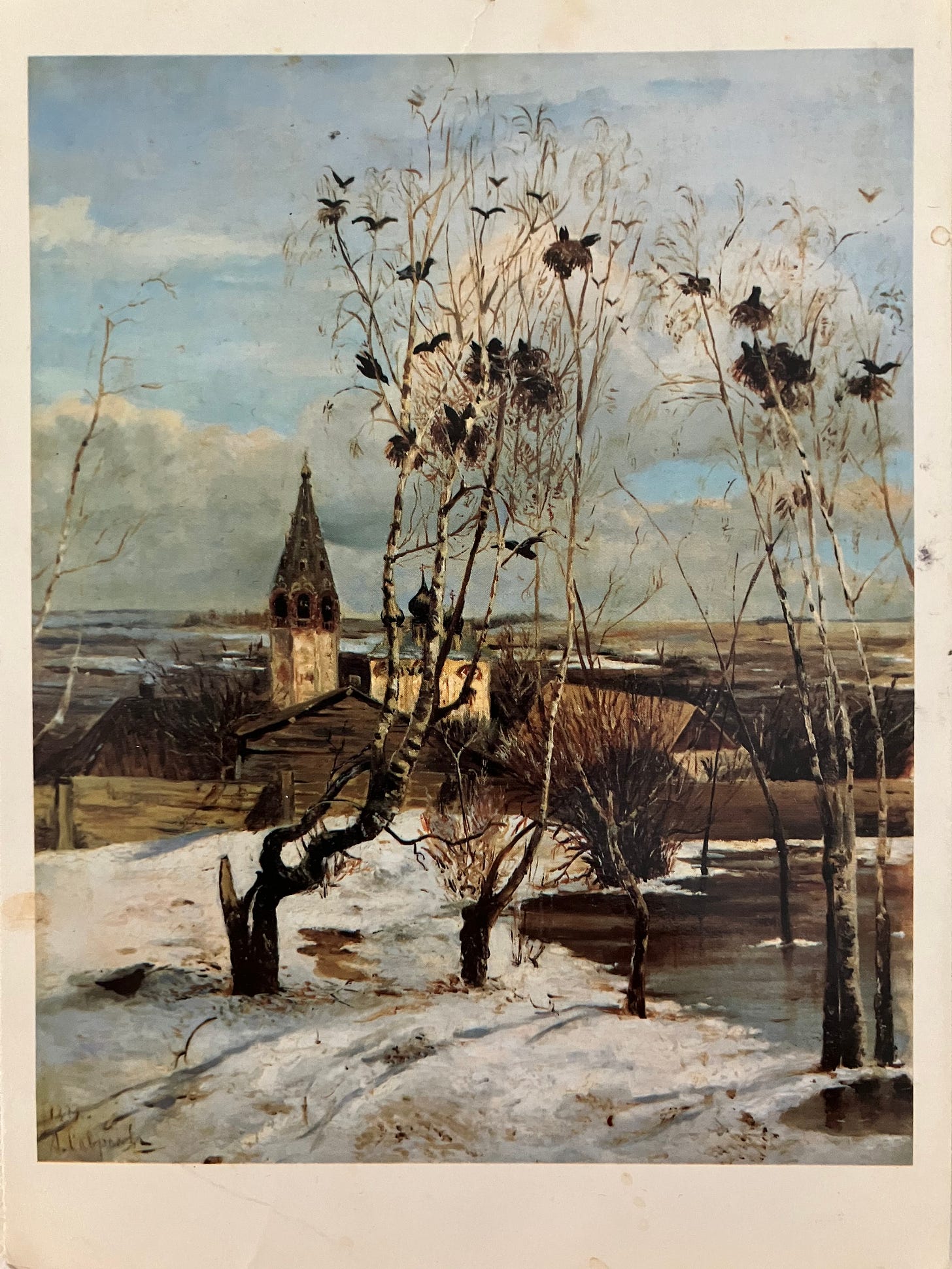

Snow blew off the rooftops in puffs like clouds from dry ice. I watched from the window, looking down. It had taken the road, the black surface fading out. It wanted to take possession of everything, and I wanted to let it. I watched the houses blur and fog in the atomising air. I had been cleaning and a sick, penetrating cold worked its way into the flat; the walls were bare, white and damp, my own igloo. There was no need to put the heating on: they were at home on the middle floor, a warm reek in the stairwell outside their flat, it smelled like a hamster cage. That should be enough to stop the pipes from freezing.

My new compatriot, my clean bill of health, my manifesto. The next day it seethed down. My fingers were cold, pinched hard from the inside: like the flesh had shrunk, all vacuum packed onto the bone, it really hurt. Trudging across the playground I saw a child’s glove frozen to the ground, flat as roadkill. There were children coming in at the same time as me. Andrew, who had been put in charge of health and safety, was patrolling in a raddled scarf and gloves and a grey face.

“Inside! Immediately!” His voice was hoarse and weak, but furious.

I followed them, slopping in the children’s footsteps. Angela was in the foyer, mopping up the brown water from their shoes.

“It doesn’t make much difference, does it?” she said. More of them trouped in - more voices, more footsteps, more dirty water.

It was boring to be at work that day - especially boring because the children were excited: a damp over-heated atmosphere of drenched children drying off, a sweaty tang muddled by screams and laughter and adults shouting.

“Year 4! Excuse me! Year 4!”

I put my things away and went to the classroom. Elaine was there - sad-eyed and beautiful, like Zadie Smith. She was a higher-level TA, but they’d been using her as a teacher while Steve was signed off with depression. She was at the front of the room fiddling with the lesson plan while the children boiled and bubbled in their hell-broth. She had that perpetual serenity, which was just irritation held at arm's length. She turned on her chair as soon as I came near.

“Do you mind filling the water-jugs, Miss?”

She didn’t need to ask - I always did it, every day, except just one time. But since then she made a point of mentioning it, as if I was trying to get out of it and she had to pin me down. The tap in the corridor was out of bounds for spurious covid reasons, so the jugs had to be filled in the staffroom. The teachers got their TAs to do it, but since Yvonne used a walking stick and Lorraine had carpal tunnel, I did it for all the classes. Every morning I made my rounds, like a milk-maid, slopping to and fro, bringing the jugs into different rooms where the teachers thanked me without looking at me, or thanked me in a guilty embarrassed way that made me wonder why they didn't just do it themselves.

Morning briefing wasn’t cancelled, but it had to be short because the children were already in. The breakfast club staff had been commandeered to stay on while teaching staff went to the hall. We stood in a big circle, an arm’s length between us for covid reasons, the headmistress in the middle like she was in a circus ring. She always wore quite spiffy trousers, which added to the effect. There was a safety notice - “There’s not much chance of the children getting out today” - teachers would have to stay in their classrooms at lunch. A lot of parents had been getting in touch to complain about the rules - from now on we shouldn’t respond, just ask them to email the head directly.

“Just think of it as vomit,” said the head. “They’re coming up and vomiting their emotions all over you. Bleurgh!”

There was something naive about her posh voice, the flamboyant trousers: today they were pale pink with a red go-faster stripe. They seemed to proclaim a faith in something that definitely wouldn't happen - some positive social change.

Outside, in the corridor, we were caught in a bottle-neck and forgot the show of social distancing, enacted in still scenes like tableaux vivants - in between, the actors milled around. The Deputy Head, Louisa Hart, fell in step beside me.

She was shorter than me, and had a sculptured, elegant head and neck on top of a surprisingly wide, bulky body. I thought of her head as the tip of the iceberg.

“Monica, could I have a word? Did you get round to filling the water jugs?”

She spoke in a hurry.

“Right. I just wanted to check. Just make sure you do it as a priority - Elaine’s been finding that the jugs are running out mid-morning, which doesn’t make life any easier. She has a lot on and she really needs your support. So if you make sure that you do it first thing when you come in?”

She met my eyes firmly. I was stung, I wanted to say to her that there was only one time I didn’t do it, and I didn’t see why I was the only one that had to do it anyway. I paused, preparing to speak, but she had already moved off towards her office. Everyone swept on around me, obdurate in their missions. Their voices melded with the din of the children waiting. Elaine walked past me as if there was a wall between us. She had a lot to do, and she couldn’t expect any help from me. She’d made sure that everyone knew that.

2.

It stayed cold that week but the snow went threadbare, clinging to corners, retreating to shady nooks. In the mornings the children were kept loitering in the playground - Andrew was kept there too, pacing the asphalt, cadaverous, resentful. The children huddled in bombers, parkas with fur-lined hoods that hid their faces. There were always a few who didn’t have proper coats and it was debated whether they could come in - no - or stay outdoors in a fleece, or if they had to wear a coat from the lost property bin. Most of them would rather freeze than be marked out in a musty jacket that didn’t fit.

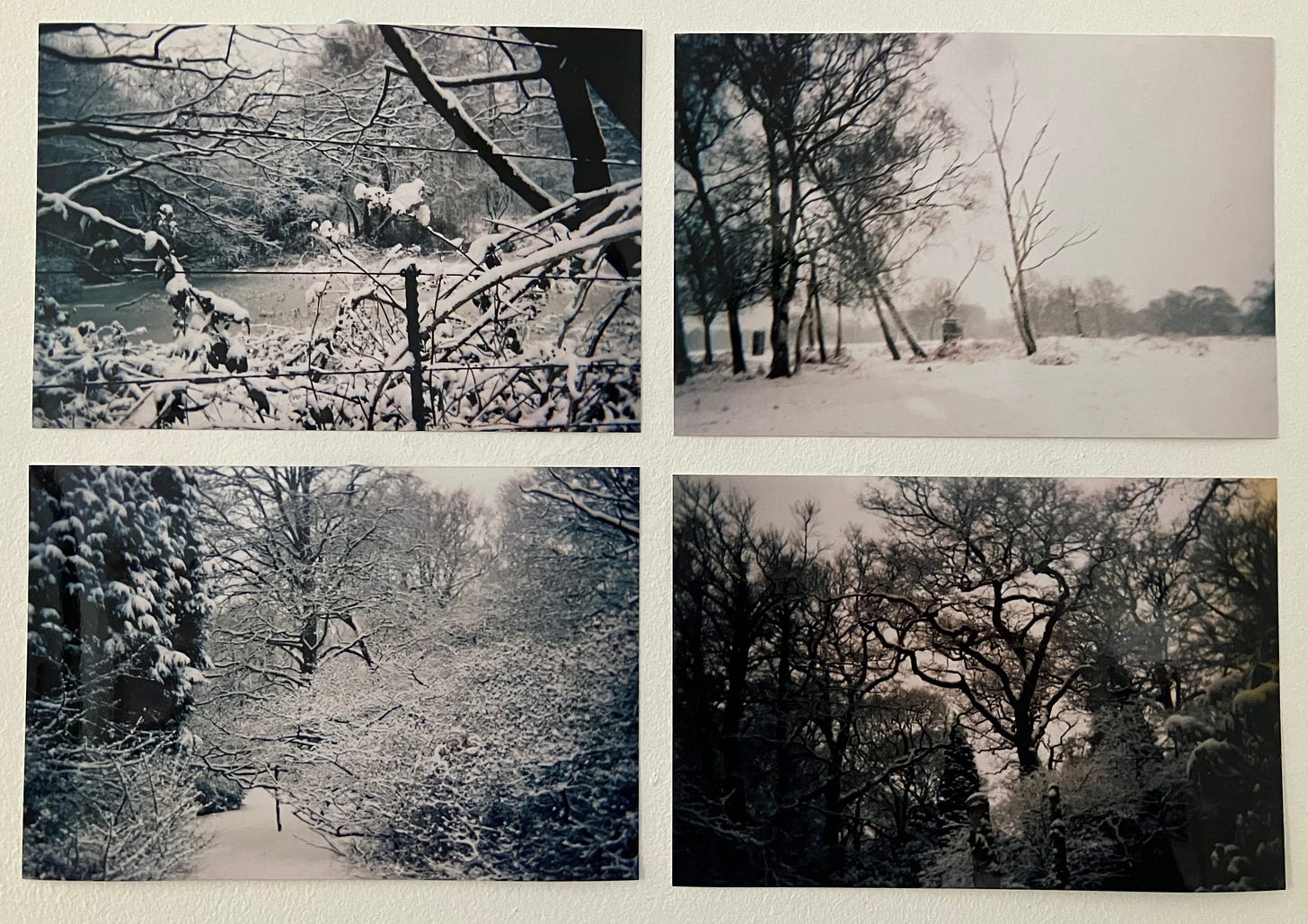

I went to the staffroom and hung up my things, then stood for a minute looking out at the grey, toneless sky, the bare branches and dirty white houses. The window was open, just a crack. There was defensive tape round the climbing frame; I could hear it creaking in the wind.

Elaine asked me to work with Magnus. He was a shifty child; clever, but slow and inattentive. He didn't like having me next to him. I had to wedge myself in the space between him and the radiator, with the table behind knocking the back of my chair and the table in front jutting into me when the children rocked around. Magnus stared straight ahead during the lesson, pretending to concentrate: a difficult performance that took all his mental energy.

The radiator was industrially huge, buttressed, painted a sticky brown, pumping out heat. I was sweating, especially inside my bra - it’s possible to get athlete’s foot under your breasts. The window panes distorted the view; jellied squares of air preserving us from what was outside. And I was a reversed baked alaska, piping hot at the centre of this cold world which I could see lying dormant, the empty playground where the snow was deserting us. I tucked in my elbow to avoid jostling Magnus. I leaned over to look at his work.

“You’re supposed to use a ruler.”

He was holding it wrong. It slipped, and the line went wonky.

“Not like that, do it properly.” I grabbed his ruler then gave it back to him. “Do it again.”

Halfway through the lesson, Louisa came in and bustled over, finely-turned head sailing above stubby legs, like a swan

“Miss Monica, do you mind doing break duty today?”

“Okay.”

“Oh good.” She seemed relieved; I started to wonder if I could have refused. “I just wanted to give Elaine a break, so she doesn’t have to go outside.”

It occurred to me that I would be going outside, in the cold, again, not that it mattered to anyone. I swallowed my bile.

“Shall I take my break now?” I said. I wanted to make sure that I’d get the full fifteen minutes. Louisa looked harassed.

“If you ask Elaine, to make sure she can manage without the support.”

Elaine said it was fine. As I was leaving she added, “Can you make sure you get to the playground before break starts, Miss? So you’re not late? Just because if you are late, then someone has to wait for you till you get there.”

The only thing she ever remembered about me was everything I’d ever done wrong.

3.

I went to the staffroom. That was an advantage of break duty: I got to go off when everyone else was in class, so I could sit alone, with the whole room to myself. Except if Cindy was there, which she was. Cindy was a playground supervisor, she also did breakfast and after-school club, picking up any scraps of employment that came her way. She had been at the school long before me, for years, always in these peripheral roles. She had to wait in the dead periods of time between bouts of work, and she often spent the time on site, or sometimes went to the shops and took her grocery bags back to the staffroom.

I came in and found her scavenging among an array of cakes and biscuits that had been put out there - someone’s birthday. A card was propped open on the table which would have explained the occasion. Something to do with the teachers, always, but they couldn’t forbid the rest of us access to the commons.

At first she didn’t talk - she had the furtive look people get when they’ve been found hovering over cakes. She chose a yellow one. I started to feel a little tempted myself, though I had brought my own healthy snack of garibaldi biscuits. I didn’t want to join her, vulture-like, picking over the morsels. I sat further away and hoped she wouldn't say anything.

She sat at the table with a sigh and started eating with a dreamy expression. It didn't look like she was going to chat. I felt safe, and raised myself to my feet (like something being erected by a crane) and took a yellow one, and a pink, for later. I went back to my chair and sampled it, looking at my phone. This was close to relaxing - in this world where I could never relax.

“That’s the problem,” said Cindy. I looked up. She was looking at me with a quizzical raise of her eyebrows. “They put these things out, don’t they? And the weight stays on.” Now the crumb-lined paper doily littered the table in front of her. She pursed her lips.

I missed a beat, then I said,

“It’s terrible isn’t it?” That was the sort of thing she’d expect me to say. “I’ve got no self control!”

“That’s the problem, isn’t it?” she said again, with that histrionic, lost look. With that weird nagging humour. She looked at me a bit too long, and raised her eyebrows again.

My second cake sat next to me. I didn’t want it any more, but I couldn’t put it back. I sat for a moment weighing the possibilities, and my feelings, and everything mounted. I had to make a decision, so I ate it, tasting the cheap dryness, imagining the battery egg mixture, the disease-ridden suffering in this stale confection, overly sweet icing, calories spreading into my body, spreading me out like a lizard’s frill. I felt hatred surge into the room and swirl between us, a current of silence.

The act of consumption had finished the conversation. I stood up to get to the playground in time for 10:45. She’d be going there too. She raised her eyebrows again, pinching the forehead between them, and stared at the kitchen unit and hot water urn opposite her.

4.

“Magnus, did you bring in your lunch box?” said Elaine. She was looking through the crate at the back of the classroom.

Experience had taught him to be equivocal, but he committed himself:

“...Yes?”

“Where is it, then?”

He looked sly.

“I don’t know.”

“Can you have a look for it?”

Magnus got up and scouted in the places where it might be - a small figure, face averted, like an EH Shepard drawing.

“It’s not here.”

“Because your mum has been complaining, hasn’t she? She’s been a bit worried because all your lunch boxes and water bottles have been going missing and you’ve been coming home without them.”

Magnus opened his mouth. His eyes crawled towards the door on his left, then to the right.

“So how are we going to deal with that?” she said.

“I ...don’t…. know.”

“Where do you think you left it?”

“In the playground … maybe?”

“Miss, can you go out and get it?” said Elaine.

This time it was a relief to be sent outdoors, given a task that took me outside the tomb of my routine. I told myself to linger, but instead I walked fast, as if charged with a great purpose. I vaguely believed that if I found it quickly I would impress her and convince her of my efficiency. I felt myself fill like a balloon with importance (so rare were my occasions) - no one was charged with this mission but me, it depended on me. I galloped downstairs and into the playground, flinging myself through the air, bursting through the doors.

Cindy was there already, waiting for Key Stage 1. I felt an urgent need not to smile at her, or look at her, not to let her speak to me, but at the same time felt a mounting anxiety that I should smile or nod. I walked briskly and she seemed to be minding her own business, in her own world, staring into the middle distance. But as I went she stiffened and I sensed a disturbance in the air, coming from her mind, and even though I’d already gone past, she yelled after me.

“Slow down, Miss! There’s no need to run! You look stressed!”

I got round the corner to the bit of the playground where the Year 4 bubble spent their breaks. I scanned it, searching for the lunchbox - I saw it in an alcove next to the boys toilets. I looked around again, pretending that I hadn’t spotted it. There were various bits of detritus on the ground - an abandoned fleece, a crisp packet blowing around. A deflated football sagged on the edge of the storm drain. Brown water clung to it, like one of those little lakes that gather in a rocky crevice up in the mountains. My face felt like another piece of rain soaked litter. The chunter of cars behind the wall breathed their pollution and the wet, dirty air belonged to those sights and sounds. I felt calm, noticing the fishbowl reality in which we were contained. Morning, boys - how’s the water?

I got to the lunchbox and picked it up. I wanted to stay another minute - no one would care, no one was timing me, not even Elaine. But some internal pressure compelled me to take big strides and hurry back.

“Don’t run everywhere!” Cindy was ready for me round the corner - she’d been lying in wait the whole time, like a stupid dragon. “Don’t stress yourself! You’ll die young!”

5.

The houses in my neighbourhood were white and low, neither especially big or small. Some were semi-detached, flush on the pavement, with small courtyards to the side. Some were set back with a lawn in front. They had a kind of uniform diversity: like a group of socially similar people with their different features, their quirks: pitched roofs or mansard roofs, white render or clapboard, square modern windows or old ones with shutters and juliette balconies. But they all managed to feel the same, and suggest the same aspirations. They made their own community. It was a very quiet neighbourhood.

The old couple next door had a cherry tree, sometimes they’d bring round cherries on a plate. They had a white cat. I remember trying to pet it - it sprang away and hissed viciously. My mother said it was a French cat, that was why it didn’t want to speak to me. There were red squirrels. In the car, on the road through the woods, I used to look up and see them leaping from branch to branch. It's foreign to me now. Manageably foreign, nostalgically foreign, like the near past.

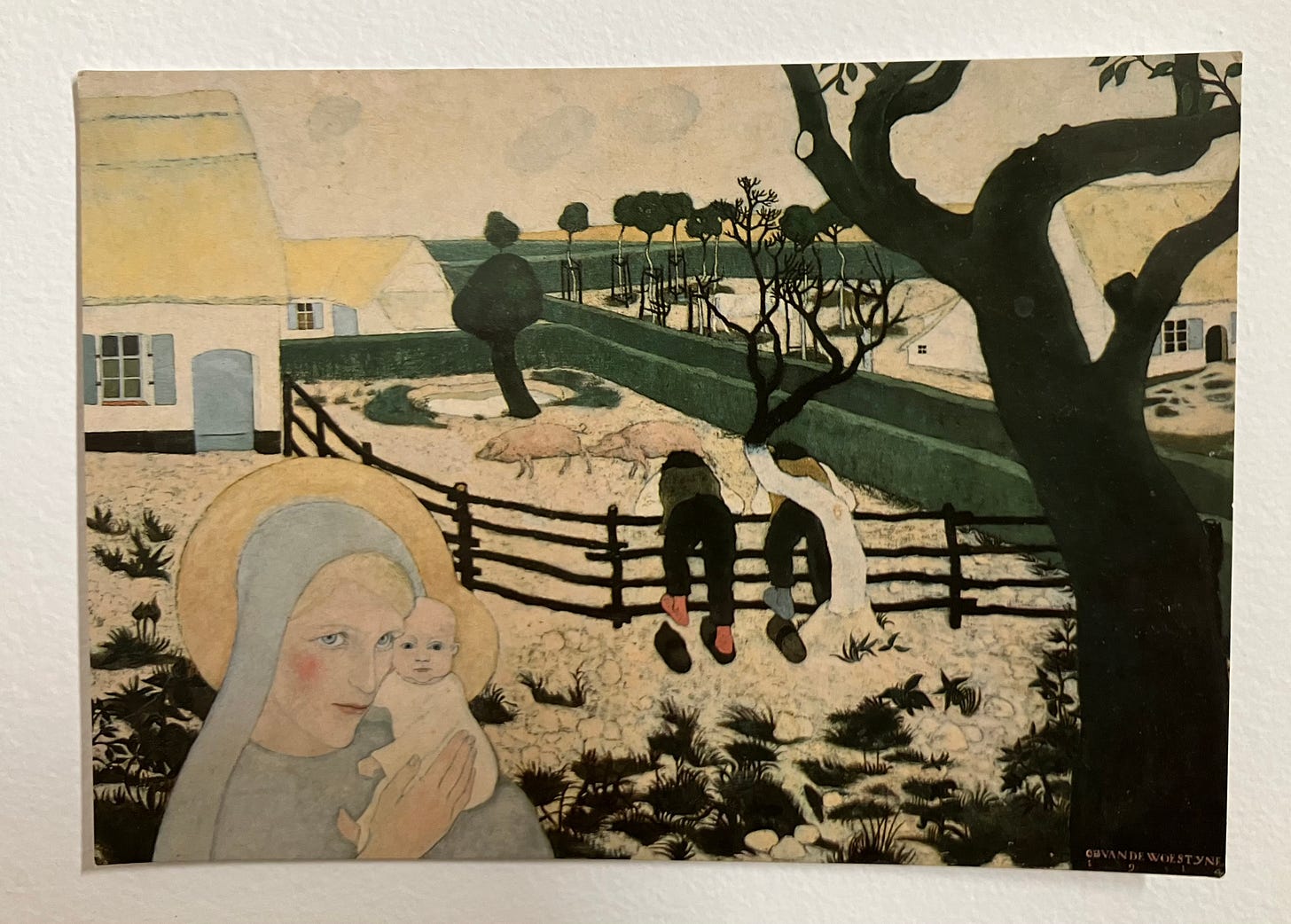

My dad speaks English at home, French at work. I asked him if he ever spoke Flemish growing up, and he said that probably he’d once known a bit. “Your mother speaks Flemish better than I do.” She does speak it, vigorously, when she’s out and about. It seems typical of him to have forgotten a whole language, but I guess he learned from people who learned to forget when they had to. His parents were refugees from Antwerp - they made the journey I take in reverse on the Eurostar, a repetition made bathetic by convenience. My mum takes a keen interest in the whole thing, of course. Last time we spoke, she was reading ‘When I Lived in Modern Times’. I asked if she’d ever read something by a Palestinian and she said that was an interesting thought, but she’d never got round to it.

6.

Sunday morning in bed, the window covered itself with mist and jewels of rain. I tipped myself up to look at something other than the sky, aching white. Things on the ground were desolate - black, wet trees, gardens disheveled, fences blown down. The empty, soaked street. I couldn't bear to go outside. It was evening, in the living room with the light on and a glowing fog pressed against the window, with a dark undertone. The shapes of shadows decorated the room. I was tired, resigned, even content. My feet were cold blocks, the warm pool below my face was a double chin, stomach squirming like some disgusting pet in a tank, loins burning mysteriously in the distance. Some fullness, some emptiness, some hope, some kind of feeling. I wanted to express something, like milk.

7.

I woke up in the night. Light pollution in my room, spoiling the dark, grey instead of black, nagging at me. A sense of objection filled me, bloating me up, strangling every limb like a tourniquet, a choking impasse, a poisoning. I turned in the sheet. Its texture filled my skin with grain, sliding and grating on my pores. I was walking along a pavement and I saw Christelle through a car window.

I went over and tapped the window. I said Christelle! Oh my god, ca fait des lustres it’s been so long ca fait des lustres so long since I’ve seen you que je t’ai pas que je t’ai pas vu. I realised that I'd missed her, all these years. She said she was sorry - she didn’t remember me. She spoke in gentle, jagged, half-coherent sentences, no more knowledge or assurance than a shy child. She said she’d had a stroke and she’d forgotten everything. Elodie was in the car, looking after her.

The window rattled. Horizontal rain outside, aspirating gusts of spray along the street - on the path of air between the upper floors of the houses. I'd been indoors all week, with a wart on my finger providing most of my entertainment - bulbous and red, warping my knuckle. I coated it with four times the prescription of wart mixture: a soaked skinless lump with patches of residue, galloping with virus. My white walls, a stain in the corner of the ceiling, like the armpit of a white shirt turning yellow. Beading of milk-like rain on the windows, thickening in spurts.

That was a sign of sickness, the dream about Christelle. Coming at me like a visitor to my lonely days - my flatmate was staying with her parents. Some random episode of the past discovered, unassimilated and unbearable, like a tumour. I remembered having lunch in the cantine - I knocked my plate and spilled food all over myself. A few people laughed or yelled. I jumped up and started trying to clean myself off.

“Are you going just to leave it there?” said Christelle. There was ratatouille on the table and my chair. “People are sitting here, you can’t just walk away, it’s disgusting.”

“I’m not leaving it - ”

“You have to clean it. I’m not sitting next to that.”

I started wiping it up. People were handing me paper napkins - I tried to laugh as more and more came - they had stains and bits of food on them already, people were throwing them at me. I wiped the table and my seat. She was watching to make sure I got it all. It had splattered on the floor. I knelt, smearing with serviettes that were too already wet to be any use. My skirt felt cold and slimy, bits of courgette dropping off or clinging on, as if I’d been sick down myself. I looked up and saw Christelle’s face, looking at me, contemptuous but elevated, energised, on one of her crusades.

I remembered other times - falling behind while she and Elodie and Laure set their pace faster, linking arms. They didn’t turn back, they didn’t say anything, I knew I was being shaken off. I remember staring at her across the table, talking, trying to make her like me. They sent her to the school psychologist in the end, because she couldn't stop bullying people - she’d even started bullying the teachers, it was like a kind of Napoleon complex.

She was still coming to school but we didn’t speak much towards the end, I have no idea what happened to her.

8.

Morning came and whitewashed my flat like a spring clean, except that it showed the dirt, the limescale on the draining board and the desolation, bare and stark, that was unfortunately there. I made coffee, toast and margarine. I ate and drank sitting on the floor to save effort. Then I had a shower, fortified to bear the water’s assault and the tiring ritual of drying my body, which does not seem inherently dry - always moist, like a marshmallow. I wound a towel round my head and another on my body like a strapless dress - probably the sexiest outfit I would wear for the rest of my life; perhaps the sexiest I had ever worn.

I’d been bleaching the mould in my bedroom. I removed the plastic bags that I’d sellotaped over the plug sockets and the carpet, and put these and the rest of the detritus in a fungus-ridden bag-for-life that I normally kept my recycling in, which had absorbed the slime of generations of poorly washed-out bottles and tins. I was keeping the bleach-plastic inside the slime-plastic till I could think of a way to dispose of them both responsibly. In the kitchen I had tupperwares of old batteries, old lightbulbs, and corks, all of which I intended to take to a recycling centre one day. They had been building up for years, for a day of atonement.

I looked around the place, in all its clutter and meanness. All of my care, all my schemes dragging me down, taking my strength pointlessly, to be added to the junkyard of wasted human effort. But if I threw it out, all the toxic plastics and chemical waste and garbage that I've accrued, it would still be there, choking out life somewhere I can’t see. Some landfill in Malaysia. I wanted to give beauty back to the world, or at least see it and preserve it, at least not destroy it. But I knew it was waiting for the day when some imperative would make me put it all in a bin bag. Some positive change.

The bleach smell was faint but sickening - it had soaked into the atmosphere. I pulled the windows open and cold clean air came in to meet all the layers of bleach and petrol and children’s farts that lined my lungs. Dear rain - you have reached a part of me that no one else reached - you made me cry. It touched you, Monica? Monica. It sounds like you want to have sex with the rain.

9.

I hate the toilet where someone comes in like a thief in the night and has diarrhoea every morning before work and it never fully goes away because of the very weak flush. I try to avoid it, but it's the only staff toilet upstairs. My face in the mirror was bloodless, dull.

Everyone was busy before briefing, hurrying here and there. I did the jugs, criss-crossing between rooms. Coming up outside a door, I heard Louisa talking to Elaine.

“- outdoors PE. But if you don’t fancy the weather you can send Monica out - ”

That’s right, send her out, like a dog. Bark, bark, I’m Monica. Hello! Are you feeling better? No, actually, I’m feeling worse. I wanted to lie low, but there was task after task, we were behind on readers, then it was maths, then I had to help the children get changed and take them outside for PE with Grant, the sports coach. I led them, cavorting in their little tracksuits like woolly dolls.

I wrestled with the door of the cage. The children crowded behind me, excited and noisy. There was an awkward sliding lock, the grill walls rattled while I forced it.

“Thanks Miss,” said Grant, shouldering past me with two sacks full of equipment, and the children jostled joyfully after him.

“Run to the end!” shouted Grant. “Run back! Grab your sticks! You're going to go weave round the cones, and you’re going to dribble!”

It had rained overnight, everything was soaked, it was chilly, no patch of sun. A comfortless day. I tried to stay busy. He always wanted me to do something but I never know what, only that if I loitered at the sides he’d start making comments, even though when other TAs came out they just sat on the bench and he bantered with them, such mates apparently. I tried to disguise my uselessness by following the children around, chivvying them.

“Magnus, hold your stick lower down, like Mr Grant said. Like this -” I grabbed at it. Grant looked at me with dislike.

“Good job Magnus,” he said loudly. “You’re doing well! Nice one!”

I didn’t know why I bothered, or what he wanted from me. The lesson dragged on - races, relays - “Who scored most, Miss?” I don’t fucking know.

“Are you watching the time, Miss?”

I didn’t know why he couldn’t watch the time - it was his lesson, he was the teacher. I wasn’t even wearing a watch. I looked round, as if there might be a clock somewhere, floating above the basketball hoop. I heard a tide of children - the bell must have rung; classes were already spilling into the playground where Cindy was waiting. We were late.

“Line up! Follow Miss!”

I strode out of the cage, a lumpy straggling trail of children behind me. They needed to get changed but they couldn’t miss break, we’d be running behind all day and Elaine would feel the need to mention it to everyone, another reason to tell everyone how unhelpful I was, and how she had to take all the burdens of the world on her long-suffering shoulders.

“Miss! Miss!”

Cindy’s voice - that nasal oboe. Suddenly I was suffocating with rage, hardly breathing. I didn't turn my head, my neck was stiff, I was determined not to hear.

“MISS!” I looked back. “You haven’t closed the gate!” She was pointing at the door of the cage, left swinging open.

“Why don’t you shut it?” I yelled. I could feel my voice, everything about me, act out the hate I felt for her, her nasty little balled up face, her pointless indignation, her querulous urgency.

Then I saw that Elaine was standing near the door. She must have come out to see where we were. I hadn’t expected anyone to hear me yell - any adult, I didn’t give a shit about the children. But Elaine was eyeing me, coldly, deliberately, like she wanted me to know that I’d shown my true colours.

10.

There was coldness coming from every person for the rest of the day. She must have told people in the staffroom at lunch. That was where they could have all got together - I could imagine it - her telling everyone the way I had spoken to Cindy. Harmless, helpless, impoverished Cindy, old faithful servant. Who they all ignored but I’d be getting the punishment, and they’d feel like they’d done something moral.

When I came in the next morning the coldness was still there. More than just being dismissed or thanked hastily and awkwardly - a conscious reserve.

We all went to briefing. I took my place in the big circle. It was running on my mind, this atmosphere, what was being said about me. It took me a minute to tune in to the Head, giving her notices.

“ - and at a time like this it’s more important than ever to speak to each other kindly. However we might be feeling, it’s not acceptable to come in here with our emotions out of control.” Her voice sounded plaintive and chiding. “And I’m sorry, but I really just cannot accept members of staff talking to each other without courtesy. We might be stressed, but I cannot accept rudeness to fellow members of staff, let alone in front of pupils.”

It dawned on me, what she was referring to. She went blustering on.

“- and I really think we owe it to each other - ”

The public telling-off. It had happened before, but not to me. Her face was pink with embarrassment and she was staring past me, no names mentioned. I wanted to puff out my chest and cry: not guilty! No, not guilty. I stood up straighter, l tried to meet her eyes. It felt like bravery, but her gaze was frozen in position, I was met with nothing.

What I was seeing started getting wet. I thought I was numb but - hot and wet - some artist, some Monet, had been daubing across my eyes. I looked round the room, but I couldn't latch on to anyone - a wall of unseeing faces. I knew I was blotchy, mortified, begging for what I wouldn’t get - pity. I’d been rude - wasn’t I tough enough to hear a few words of criticism? I’d been hurting people, but I wasn’t brave enough to carry a bit of hurt myself. Couldn’t even bear this negative punishment: so polite, so distant. Well, if you aren’t looking at me then you aren’t looking at this.

Tears fighting at the back of my eyes, pounding them. Heart drumming like someone was beating it with a stick. Face like I was branded. Monica, you’re ugly, you’re stupid. No one likes you. Look what you’ve done.

I almost forgot to move when everyone started leaving - they were circulating around me. I joined in the flow that went down the corridor. My vision still wasn’t clear - like I had a heavy cold, I made the excuse to myself. But the six weeks of sick leave was nearly over. Soon Steve would be back, whether he liked it or not: impatient but basically uninterested in me, shouting at the kids, short-tempered, unpleasant. I much preferred him to Elaine.

At the end of the day I walked out and spurned them all. I left them, symbolically. A private drama, enacted for my benefit. I knew I’d be back tomorrow. I knew the whole incident would be, not forgotten, but absorbed into a general muddle. My life, and Cindy’s, the school, the road, the borough, a fabric made of every quarrel, and everything else.

I went home, took off my shoes, watched TV on my laptop. I made myself a heavy dinner - potatoes in cheese sauce. I made enough to save some for another meal. But I had seconds and, inevitably, thirds, and then it was all gone. I sat back down in a stupor, the frenzy over. I played the next episode. While I watched it, the food expanded in my stomach - my stomach journeying in the dark like a submarine, facing unbearable pressure. I wondered if I’d have to call an ambulance.