Joyriders

I woke up and rolled into a deep gulf of misery, as if I’d been sleeping on the precipice and waking up had knocked me in. Tears were running down my face, for no reason that I could think of. The world was absent of any detail, any information apart from this terrible despair, which was blank, like there was no need for a reason.

“I feel so bad,” I said.

“So do I.”

That came as a pleasant surprise - I hadn’t expected him to be feeling the same. I hadn’t expected anything. The world was filling itself in around me. He looked bad - his skin, his eyes, his sickly expression: suffering but friendly. His hair looked bad too. Actually, it did me good to see my inner state mirrored. Like seeing a chimp in the zoo when I was a chimp myself - seven years of age. I put my hand on the glass and the chimp did it too, palm to palm, touching in a way, and this foiled connection made me happy at the time and has made me sad ever since.

He was on the floor with his head on a pillow that I’d thrown there, though sometimes we did fall asleep lying on the same bed or sofa. His attitude was limp like an invalid, but it seemed self-conscious. I was interested in the chemical nature of my emotions. At first I’d been worried that I’d tapped into some fundamental truth underlying everything, something I’d been ignoring this whole time. But my heart started to lift. He started crying - he turned over to wipe his face on the pillow.

“We just really need to do something nice today. I just really want to be positive.”

He started looking at trains on his phone. The memories of every excellent day we had ever spent together flowed into me like physical strength.

“I just really need to eat something but I can’t.”

We’d got takeaway the night before but we never opened it. It was still on the counter, like a packed lunch lovingly prepared by someone’s mum. My mother took care of me studiously and loved me diligently, like an assignment. I liked the way he always looked up transport and worked out where we needed to go - he really pulled his weight that way.

“Okay, I just don’t want to miss it -”

“Yeah, I’m nearly ready -”

“We need to get on, now -”

“I know, just one minute -”

He didn’t want to throw away the joint - nothing was more important to him at that time, it could have been glued to his fingers. We were in the underpass, trains reverberating the damp concrete.

As it happens I was right, we barely made it: jumping in through the doors when they almost closed on us, coming in hard like someone jostling you to start a fight, I had to push back, I was sweating, shaking, I really hadn’t needed to run, trying to catch my breath, almost fell into the seat as we started moving, as the crumbling fag-end of London stepped away and the train started its long march towards freedom. I saw a graffiti on a wall that said ANUS, like a secret message, like an accusation. We slid past and left it behind us.

“I don’t know what it is that means you need to smoke at the exact moment - the exact moment -” I realised I was crying. At the same time I realised that if I didn’t have a friend like him today then I didn’t have anything. The train shuddered to hold us. I looked out of the window. The sky and the town and the country shuddered to hold the train.

Tantalising green was all around us but we were stuck on its borders and couldn’t get in. I didn’t see why we couldn’t walk across the fields. Morally, I didn’t see it - on a practical level there was barbed wire and hedges along the side of the road. Even the tall dark trees were part of a deliberate palisade. It was as if we had accelerated into spring, pressed fast forward on the seasons and travelled to spring’s native country, but even here we were choked off, and we couldn’t find the footpath.

“It’s strange to me that you’d say that you know the way -” I said.

“I do know the way, it just took me a minute. And I didn’t notice you helping -”

“I didn’t come out here saying that I knew the way.”

“So you basically expect me to conduct you around. Have you ever noticed? It’s not the behaviour of an adult.”

“I don’t even know why we came here. If we’re not going to do it right, it’s better not to do it.”

“Okay, cool.”

He walked on quickly. I stopped to identify an interesting leaf on my app. The mud path was dry, like my throat, I had a sensual desire for blackberries, hazelnuts, dew - all the comestibles of nature that should have been there, hidden behind tiredness and anger and the way things had turned out.

I got to the end of the path and went over a style. I heard little bleats. He was leaning on a fence, staring at the lambs.

“You can’t look at them and be sad,” he said.

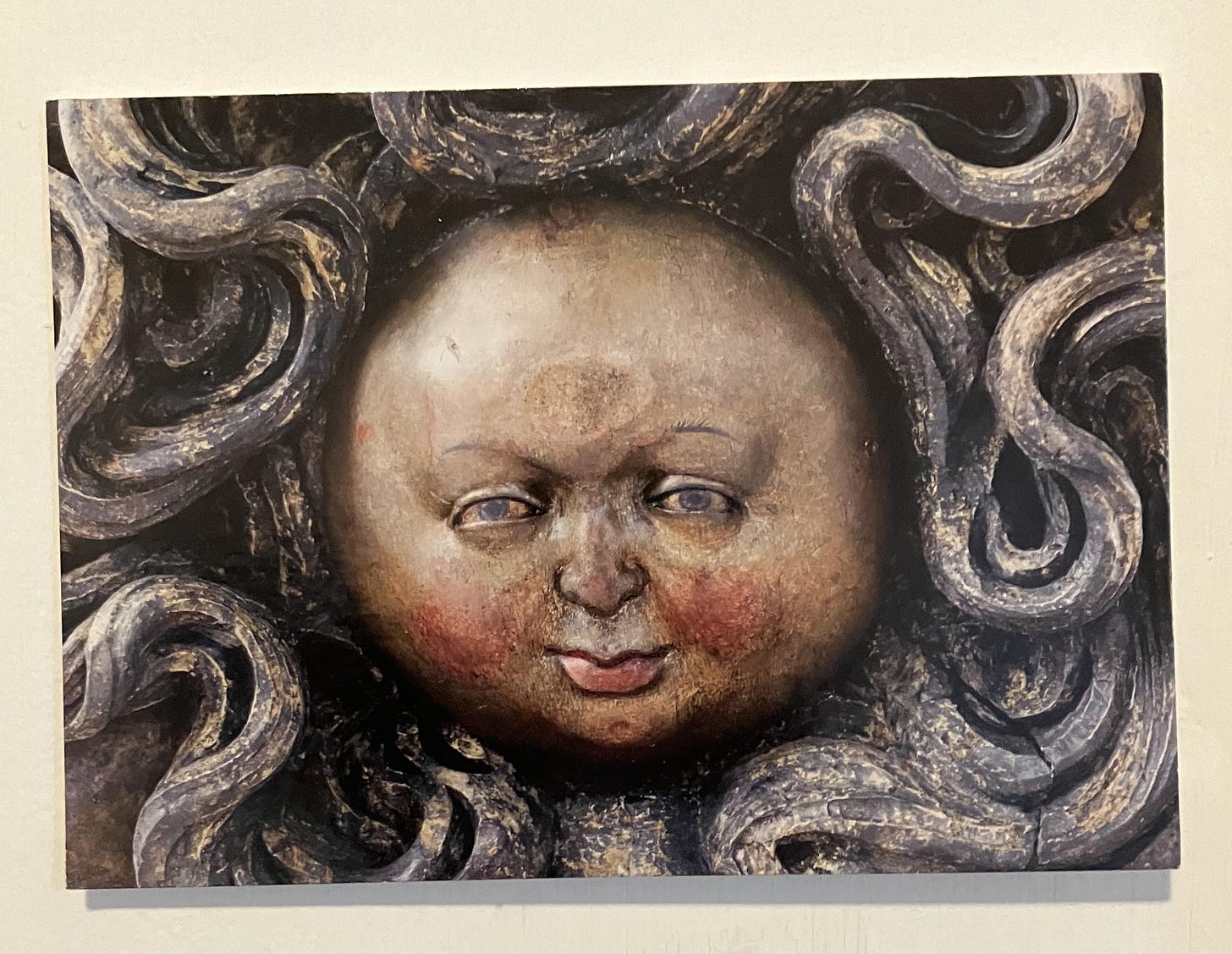

“No,” I agreed. We both started crying. The lambs made thin bleats and a ewe bellowed back in the voice less of a man than a god - some fruity god, drunk and horny. The lambs were running in pairs, on wooly diagonal legs. They looked at us with their pharaoh eyes and laughing smiles. We smiled back.

“Look, there’s another sheep and it has a lamb -”

“It looks angry.”

“It’s not -”

It lowered its head.

“Oh my God!”

It thundered towards us.

Jessie’s parents live outside Taunton, so the plan had been to go down the day before to be in time for the funeral the next morning. They’d booked a room at a hostel for her friends. It would feel bad to say it was inconvenient, but if things are hard that inevitably plays out in terms of what happens. I’m not the sort of person that lets logistical problems hold me back. We’d booked places on a coach, we just hadn’t thought about how long it would take to get to Hammersmith, but there was actually another coach that left at midnight and got there at four in the morning, so that was the new plan. He said he was nervous and did I want to do some MD? And that - the suggestion itself - made us both relax, and dissolved the tension and the hesitancy that had been building up.

I watched him grind the crystals nice and fine but there was still a roughness I could feel, and a roughness to the whole experience. There was a smile that went through my bones. The decision had made itself. Now it was irreversible. The evening was opening up. I could feel all its possibilities, the way it was hanging in time, like a ruby on a necklace. My eyes swallowing everything. The same blood coursed through both of us: a reciprocal transfusion like the decision had made us blood brothers.

I wasn’t thinking directly about the way that we might get judged. I didn’t care what people said about me. You’ve got to live according to your lights. That’s not to say you’ll always do the right thing. Something that makes sense at the time might seem different later on.

Like when Nice Jen’s boyfriend told her he cheated on her then left her, then she lost her job all in the same week. She texted me and said what had happened and I replied,

Ah!!! That sounds shit

Stay strong

I didn’t follow it through beyond that because at the time it seemed it would be wrong to give into my own curiosity and, almost, glee that a thing like that could happen to someone as good as her. So I let the air clear, then about a year later I messaged and she never replied, and she never spoke to me again. A while after that I understood that I shouldn’t have been thinking about my own motives, I should have been thinking about how she felt and what she needed from me. So then the fact of her not speaking to me and even telling third parties that she disliked me seemed fair. But I still held some rancour towards Nice Jen.

“Shall we do some more?”

It seemed like an incredible idea.

“I think it’s better that we didn’t go. I just think, if you’re not in the right frame of mind, it’s kinder not to -”

“If you go from a place of inauthenticity -”

“You’ve got to be feeling authentic. That’s a basic requirement -”

“And just cos you feel bad doesn’t mean you’re doing a bad thing. It actually means you’re a good person because you’re thinking about whether you should feel bad.”

“What’s actually bad is what my cousin did. Did you know? My cousin refused to go and see our Gran when she was in hospital, and she had cancer, and she kept asking to see him but he wouldn’t go, he said he was scared, apparently, and then she died and that was it.”

“That’s really bad. How old was he?”

“Eight.”

“He sounds like a dick. But this isn’t like that. I mean, she’s already dead...”

“It’s not like we’re offending her.”

We crumpled at the edge of a field. It wasn’t a particularly nice one - the grass was scratchy and it smelled of manure. His face was going in spasms and I was like him, I could feel the backwash of every chemical in my system, rinsing me, wringing me out. I hadn’t eaten in 24 hours, I was weak, burning like a wet fire. I had the take-away in my rucksack. But when I opened my bag I saw the lid had broken off the tupperware and inside my bag was now a sea of noodles, like those tubs of worms that fishermen have. I almost started to cry looking at it, and he said “What’s the matter?” Then he looked in my bag and screamed “NO!”

I put my hand in the bag and closed my fist on the worms.

“I’m not doing that, I’m not going to do it!” There was panic in his voice.

“You’re going to have to.”

I didn’t want to either. I almost couldn’t bear it - eating like a pig out of a bucket of swill. But I couldn’t go any further without food. I tried not to think about the places my rucksack had been - the floor of every public toilet without a hook on the door.

He was sitting with his head between his knees, held in his hands. He said,

“Why do I have to feel like this? I don’t want to feel this way.”

My spirits buoyed up. He said,

“I think we should have gone.”

I said,

“If you think about who was there - her parents and family and stuff -”

“I really didn’t want to see her parents.”

We had met them once - we stayed with Jessie for a couple of weeks one summer, and one night we came back late, and when we got back the doors were locked and the lights were off. Obviously we weren’t going to wake everyone up by ringing the bell, so we climbed onto the garage roof and forced a window, and in the end accidentally broke the window and also his foot went through the roof, which was very weak and old, and after that, from the way her parents reacted, it was clear that we couldn’t stay any longer. It felt hurtful - I remember trying to gather up some pieces of my dignity when Jessie asked me where I’d be moving on to - it was like cradling broken glass. It was important that I didn’t show any hurt or ill-feeling. I’d been trying to follow my own rules of delicacy but in doing that I’d violated other, pettier, rules.

I think - and I get the sense that everyone else thinks this, too - that I’m the guilty one. He’s clean in a way that I’m not. It’s not that he behaves differently, but he acts out of an unreflective state. He’s easier to forgive, or just to discount as a moral actor. But he’ll stick with me, and I will with him, and we’ll keep doing the same things. There isn’t anything else that either of us is going to.

We found our way out of a wooded pit of dead branches and dry brown leaves on the ground, two seasons behind. We headed uphill. The chalk was soft underfoot, cut in white tracks across sweeping slopes, under harsh clumps of gorse with flowers that smelled of coconut. We came to the crest and more and more and more of it was laid around us, like a trick, taking us off balance, all this plentitude rolling away.

There was a slight, disturbing breeze, and everything became more beautiful at such a pitch that we realised it was going to rain. The sun glanced off the long grass, the clouds made shapes. The ozone smell - the displacing smashed molecules of the earth releasing their scent!

“Shit! We should have taken our coats!”

“Crap!”

But the rain was so slight, softening things and gently cooling us, and the haze and the mud were so bright in their dark way. It was like a fever had broken. This hooded, lambent atmosphere reminded me of a vision I’d had last night a few drugs in, a sort of half dream that I was looking at a sculpture or a rock made out of some meteorite substance, older than the earth, standing on a beach, and while the sands eroded beside it, the rock stayed the same. The rock was me. He was in the room, but some adventures of the psychonaut take you further apart, though some bring you together. He was too humble to have an isolated, megalomanic thought like I was having. He’s innocent compared to me. He’s like a lamb. I’m marmite, I’m moldavite - not everybody likes me.

When we were out of the open spaces it felt abrupt - we were in country lanes lined by hawthorn bushes that were leading into the town, and the walk was nearly over. Everything was garlanded with little white flowers as if in preparation for a wedding and I stood up straighter, like a bridegroom or a best man. The air had cleared. It’s done now anyway, no changing things now. It’s still spring despite you. Ash heart, broke heart, sweet heart. It’s spring for us.

So we felt the same: sad and happy, happy and sad. We got into town and went towards the high street where we found a dank, gloomy pub that suited our mood. It smelled of ketchup and of palpable dark. I ran my hand across the table and felt wood grain and salt grains, stickiness on the surface.

“Do you remember the dream?” I said.

“I don’t want to talk about it!” He started crying. I started crying too, in an automatic process, like a carwash, like soft refreshing rain.

“I just think that what happened to Jessie was so sad,” he said.

It was.

The afternoon was at its peak and at its end. The sun drew slanted shadows on the pavement, which made it harder to cross, like a chessboard that required us to calculate our next move. The beer had refreshed us, and cast its comfort back over the whole day, strengthening us. We were ready for the journey - we just needed some more beer and crisps and peanuts for the train. An old man had left his dog outside a newsagent’s - a border terrier, who lay, stout and bristly, where the light overspilled the shadow in a pool like honey. What a face! My God, we mooned over him! Caught in the sun, all three, us orbiting him.

His face was wrenched open in a helpless grin. His tongue lolled out, his eyes filmed over, his limbs stiffly stretched, and he made emphysemic rasps with each pull of his chest, up and down to serrated breathing - basking and sleeping in the sunlight of absolute bliss.

Jessie used to tell me her dreams in detail and I’d say mine -

Back then we never had anything we needed to do or think about

So we had leisure for long talks about anything at all.

The dream, she said, showed a waiter, an old man who works in a cafe

Opening onto a cobbled square. People sit drinking coffee,

The air’s full of talk. In a tank tall as a building

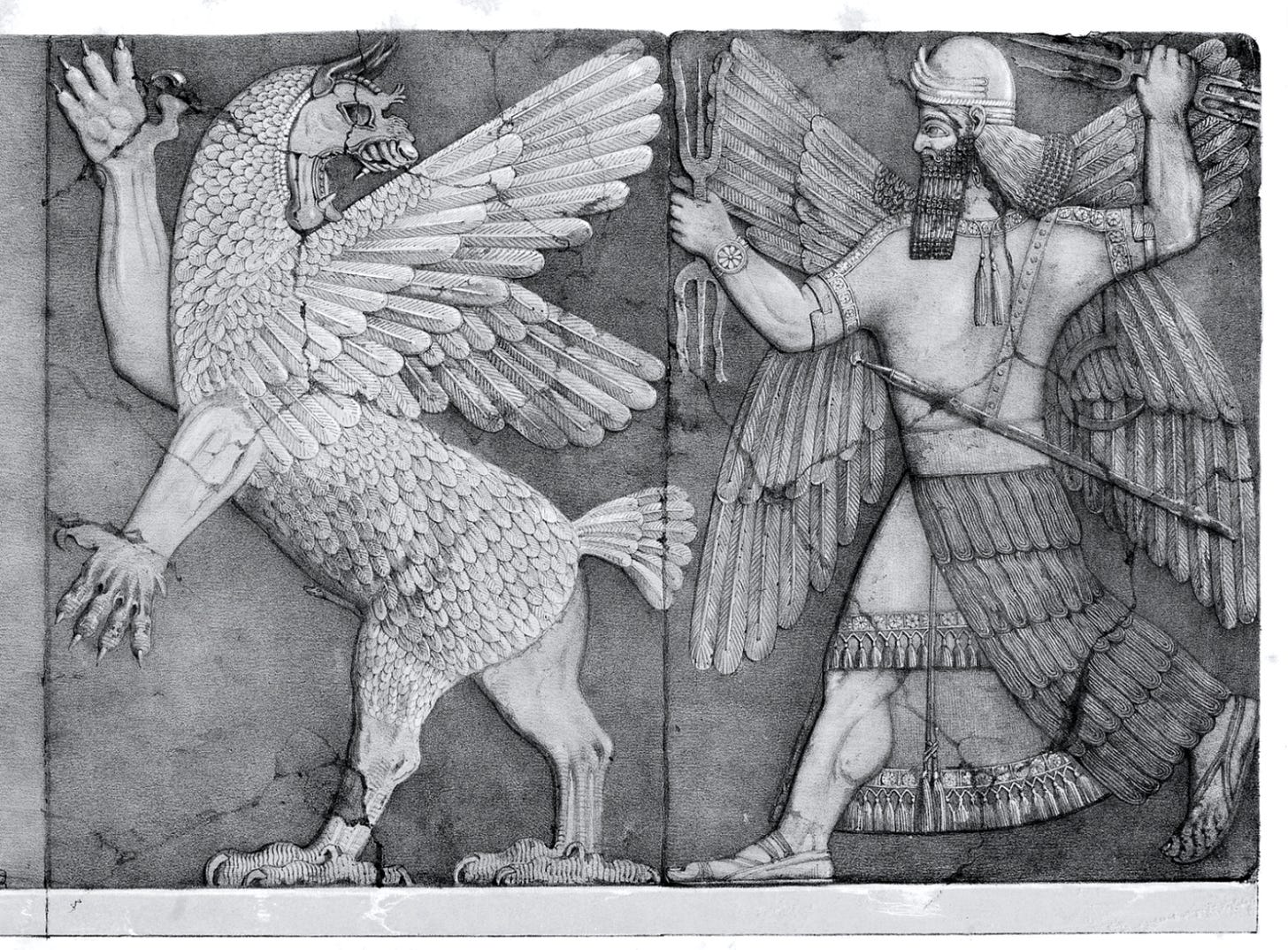

Full of water, the man’s son is waiting,

Suspended, for any opportunity to die. Life has no meaning

for some of us, says a voice in the dream

(that voice is the dross that accumulates in your head).

The man looks up and leaves because he has customers to attend to.

The son looks up and suddenly he realises that life is bliss.

Beauty fills him with fearlessness

And certainty, a surge of uncontrollable joy.

He shoots upward, bursting to the surface. But

Revelation reverses. Intention ashes into despair.

As he rises, he changes, ranging from youth to age,

A moment makes a rise a fall, flashes the fall like an x-ray

Shows a skull. He dives down and smashes on the pavement in putrid foam.

In the doorway, the old man drops his tray.

The cups and the coffee break on the cobbles

Like waves which is when Jessie woke.